How to avoid the problem, and how to avoid being part of the problem

By Sharon Thatcher

What makes good metal? That’s not easy to answer unless you’re willing to understand metallurgy. But, simply put, the making of good metal relies on the type and quality of alloys used, the heating, cooling, and handling processes, and proprietary systems that are company-guarded secrets.

For these reasons you need to be able to rely on your coil sources to help assure that the quality and adequate quantity of metal you thought you ordered is the quality and quantity of metal you actually received.

Running Short

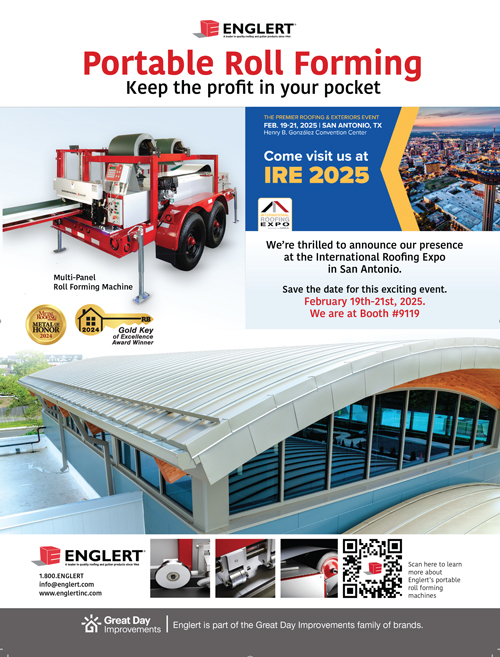

What owners of roll formers, both portable and in-shop stationary machines, may not know is that there are allowable ranges of weight in every gauge and not taking that into consideration when ordering can cause unexpected shortages.

“Ordering roofing material by the pound and selling it by the square foot can be difficult when there are allowable ranges of pounds per square foot,” Ken McLauchlan, Director of Sales for Drexel Metals based in Colorado, explained. “You could be planning on coils be a pound per square-foot and the coil sent is within tolerance at 1.08 pounds per square-foot and all of sudden you are 8% short of the material you need to complete the project and get paid.”

If you do run short, are you getting a new roll that is uniform to what you have been working with? McLauchlan offered an example of what he experienced in a previous job while working for a major roofing contractor. The contractor changed mid-project from working with pre-fabricated panel to roll forming his own panel on site. The coil they were shipped was dramatically harder than previously used and needed for the job. While quality steel, the harder steel created excessive oil canning.

On the subject of oil canning McLauchlan said, “some of that can be the [roll-forming] machine — the machine not being adjusted correctly; some of that can be the coil — the coil being harder than it should be; or it could be the consistency: and consistency could be grade, it could be gauge, it could be thickness, it could be hardness.”

Inconsistencies are a potential when working with multiple suppliers. Not to say that the quality of steel is poor, but the calibrations and testing done by each manufacturer are in alignment with their own machines and their own requirements. This applies to the steel source, as well as the company that adds coatings and paint. They can all fall within the industry tolerances / guidelines but the resulting variations from one source to the other can reflect on the final product when mixing and matching suppliers.

“The biggest issue from our standpoint, for a finished product, is that [the process and testing] has to be consistently sustained,” McLauchlan said. “It’s when you have inconsistencies that it becomes an issue.”

When there’s a problem

What happens when there is a problem on the job site with the finished panel? Hopefully it is caught before installation, but unless the problem is obvious, and the roofer is diligent about quality control, it could very well not show up until after the roof is installed.

If the customer is the one to notice that wavy panel or color variation, the first person they will call is the contractor. The contractor should call his panel supplier or, if owning a roll former, his coil supplier. In the best case scenario, the panel or coil supplier will have the means to evaluate the situation and start the process of correcting it, even if it is the ability to point out that the problem is with installation, not coil. “Whether it’s a big company or a guy working out of his house and garage, he needs a manufacturer standing behind him,” McLauchlan said. “The general contractor and the owner are looking at the roofing contractor like they created the problem. Hopefully the trend is that the supplier, the manufacturer, will provide extra material or support.”

As a case in point, when Drexel is called in, McLauchlan explained, “we go to the job site and say ‘hey, what is contributing to the issue, is it a substrate (decking) issue, is it a hardness issue or whatever; we try to be back-office support … When the manufacturer shows up, it brings credibility.”

When a problem does arise (as it surely will some day) there are a host of issues to be examined of how that panel was handled from Point A to Point B. For roll formers, the questions will be asked: Where did you source your equipment; was it adjusted within machine tolerances; was it the right profile for the job; did you buy the right gauge of material with the right hardness; does the metal have testing to support what was needed?

“Nobody needs testing and support until there’s a problem,” McLauchlan said, “and then it’s usually because somebody is saying ‘I’m going to get an attorney and you’re not going to get paid.’”

Warranties

Having the proper warranties in hand for your panel is a way of covering your own responsibilities when things go south. A typical base metal (red rust perforation) warranty is provided by the mill. A film integrity warranty is provided by the paint company. Some suppliers, such as Drexel, will combine the warranties into one, but that is not a universal practice. Realizing that you don’t have both can create serious headaches.

“A lot of warranties you see in the industry are prorated or non-prorated (inclusive of the substrate or just film integrity warranties),” McLauchlan said, “and this is one of the games that companies play. They’ll say they’ll give you a film integrity warranty. Then you have a failure, and the metal substrate supplier says it’s not the metal, it’s the paint; and the paint guy says it’s the metal because it wouldn’t adhere. They point fingers at each other. There’s nothing worse than having a bunch of people on the job site pointing fingers at each other.”

Developing partnerships

There are many processes all along the line that can be blamed for problem panel, from the contractor installing the panel, to the roll former who rolled the panel, to the roll-forming machine used to create the panel, to the paint and finishes applied to the coil, to the mill who created the coil and created the steel to make the coil. It takes strong partnerships to quickly resolve any problems before they get out of hand.

McLauchlan strongly urges that you develop strong partnerships with companies that provide you the best service for your panel and coil. The proper warranties will be passed to you through their channels and they will also, if good partners, have the resources to stand behind those warranties. Instead of worrying about multiple warranties from multiple sources, a good partner will help corral the warranties “so if and when there is a warranty issue,” McLauchlan said, “it’s one warranty, one guy to call, or as we say in the industry, one throat to choke.”

Streamlining warranties can provide a level of confidence you can sell on. “The biggest thing you have is your reputation,” McLauchlan continued.

If there are reliable partners behind you, through problem review and resolution, it will speed the response and ease the overall pain. Instead of being part of a yelling match on a job site, you can help provide a calming affect because problems are being handled.

How to Avoid Being Part of the Problem

Everyone along the supply chain is responsible for being a good partner. For a roll former, step #1 is to buy good quality product from a reliable source. The greatest temptation is to go the cheapest route possible.

“I’m all about trying to be cost effective,” McLauchlan said, “but where you’re outweighing yourself is when the problem costs 10 times more than the savings. That’s like buying material that’s on sale for 10% off and putting it on your credit card at 20% interest.”

Having the best coil is useless, however, if you don’t handle it properly. Good machine maintenance, routine inspections, proper profile selection, and more all play important roles, and all are part of the roll former’s responsibilities.

Make sure that you are in full compliance with the expectations of your customers. “Let’s say you had a coil that was too hard, or wasn’t split correctly, or non-uniformity that was causing distortion in the panel, that’s going to fall back on whoever turned the raw material into a finished product,” McLauchlan said.

You may be tempted to blame the issue on your machine. It may be justified, but don’t rush to judgment, look at your own process first: did you follow the manufacturer’s instructions? Was the machine being used and maintained correctly? Did you select a coil that was too hard; too soft; seconds; slit/recoiled/handled incorrectly; stored outside; wet; or damaged?

On the job site, do you use a seamer? Roofers need to make sure the calibration is in line with the job. “With mechanical, closed panel, it’s really important to be sure your seamer is calibrated to the panel you’re running,” he said.

You may be told it is calibrated, but is it? “With seamers, so many people buy one, borrow one, rent one,” McLauchlan said. The problem? “Everybody wants to be a mechanic,” and when the user starts tweaking the machine to their own use, it may no longer conform to manufacturing standards.

The old adage to measure twice, cut once works also with anyone using a roll former. Length is important, but so is the width. Simple template gauges or a steel tape measure, can be used to quickly check profile dimensions.

Bottom line, make quality control a required part of your daily operation.

“Every successful business has a process,” McLauchlan noted. “From the roll forming side, if you have a problem [on the line] STOP. It’s hard to fix something that’s been processed … be willing to stop and say ok, what’s wrong?”

Going any further will only waste more time and money. He uses this comparison: “The minute you cut the 2×4’s, you can typically not take them back to the lumber yard.” RF