By Kenneth P. Lambert, Jr.

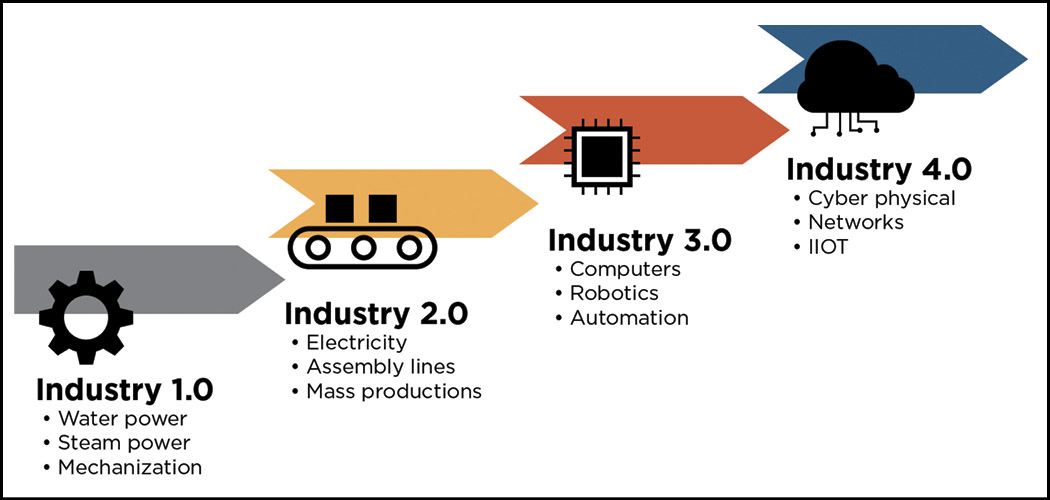

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus is quoted as having coined the phrase “The only constant in life is change.” Change is always happening, whether or not we want it. In the manufacturing realm, as with nearly every facet of the business world, we hustle to stay ahead of changes in markets, economic conditions, and other forces beyond our control.

However, there is a form of control that we can, and should, assert. This is self-directed change for the better within our organizations. How do we spark and steer positive change in a deliberate, thoughtful manner? There is a term that may be familiar to some manufacturing professionals: kaizen. This term is based on the Japanese words “kai” (change) and “zen” (for the better), yielding “change for the better,” sometimes interpreted as “continuous improvement” or “working every day towards an ideal state.”

Naturally, this is the kind of change that we all hope for, but there is more to the term “kaizen” than wishful thinking. It has come to mean “a systematic approach for business improvement” and it requires leadership, commitment, and self-discipline. Gemba Academy, a training organization focused on continuous improvement, states that it is essential for organizations to develop a “culture of kaizen” if they expect to achieve long-term success in their continuous improvement efforts. In the words of Kaizen Institute founder, Masaaki Imai, “Everyday Improvement. Everybody improvement. Everywhere improvement.”

The concept of kaizen emerged in the years following World War II as U.S. forces assisted with the rebuilding of Japanese industry. Given the shortage of time and material resources, immediate, drastic improvements were not feasible. Instead, they took an approach that emphasized incremental, continuous change. A key element was to engage the existing workforce, capitalizing on the hands-on, problem-solving knowledge those workers possessed.

There were lessons to be learned from this moment in history. Can an organization make significant improvements in their operations, despite having limited resources? Toyota found that the answer was a resounding “Yes!” In fact, the idea of kaizen became closely associated with the “Toyota Production System” — a set of management philosophies developed by Toyota to eliminate waste. This set of principles, which place great value upon engagement from individuals throughout the organization, is outlined by Jeffrey Liker in his book “The Toyota Way — 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer.”

Jikoda

A mindset which entrusts and expects employees to become confident problem-solvers has concrete and immediate applications for the small manufacturer. The Toyota principle of jikoda — stopping the process to correct problems — illustrates this mindset. Jikoda not only empowers, but in fact requires, employees to halt the production process the moment they see a problem. The problem might be a defect in a part or a deviation from the standard. It seems counter-intuitive to regard a production shutdown as a key to reducing waste. However, if production continues while a problem goes overlooked, or concealed, then the problem is compounded down the line in the form of failures, unscheduled maintenance, wasted material, or a damaged reputation. Encouraging employees to halt production when a flaw is detected yields long-term rewards. It prevents defects from becoming inherent in the end product. It also gives the employees a sense of responsibility, truly engaging them in their primary activity: delivering value to the customer.

Heijunka

Similarly, Toyota’s concept of heijunka seems counter-intuitive at first. In an environment where just-in-time delivery of products is deemed the ultimate “lean” approach, heijunka suggests that leveling production volume and product mix is preferable to wild, reactive swings in production flow. Systems that react strongly to peaks and valleys in demand tend to cause intervals of under-utilization and over-utilization of equipment and human resources. The last thing a manufacturer wants is idle equipment, but they also do not want the failure of over-stressed equipment to cause unplanned shutdowns. Firms seeking to create a “culture of kaizen” should also minimize circumstances that lead to over-stressed, disengaged employees who no longer seek improvement, or call attention to production defects. A moderated volume flow may at times require customers to wait for product, but also guards against unplanned shutdowns and unwanted quality shortcomings. These outcomes both add value for your customers.

Kaizen Event or Workout

Another way to view kaizen is in the form of a “kaizen event” or a “workout” — a 1-5 day process designed to capitalize on the hands-on experience of the participants. Dr. Richard Chua, professor, and certified Lean Six Sigma trainer, defines a kaizen event as a “well-organized, structured, and facilitated event to improve a work area, a department, a process, or an entire value stream.” With a “culture of kaizen” as a foundation, a kaizen “event” seeks to engage stakeholders across the organization.

A kaizen event makes sense when a quick analysis of the problem is possible and immediate improvements can be made using simple tools, without requiring rigorous data analysis. To get the most out of this time investment, a kaizen event should take place under the guidance of a facilitator trained in operational excellence tools. The facilitator guides the process so that the right questions are asked, and the time is well-spent. First, the objective and the scope of the event must be defined. For instance:

• Introducing quality checks and accountability into the process (Jikoda)

• Refining workflow (such as applying the principle of Heijunka)

• Identifying the root cause of a recurring quality problem

• Streamlining equipment setup

• Re-organizing a work area to improve efficiency.

It cannot be emphasized too strongly that such an event hinges upon people. It is a people-driven and people-focused exercise, so the right individuals must be invited to participate. This includes the operators, shop-floor workers, and other stakeholders who can supply unique insights. Others in the value stream can bring a variety of perspective. Even customers may be involved. These are the very people who rely on the value created by the process in question, so their participation can be extraordinarily powerful.

Once a desired business outcome is defined, then a variety of problem solving techniques may be employed. For example:

• Mapping the flow of parts or transactions throughout a facility to understand what is actually happening

• A “Gemba Walk” — walking the production floor (Gemba = “the place where value is created”)

• Process and value-add analyses to determine what steps do or do not add value

• Developing cause/effect diagrams

• “5 Why’s”— asking “why” a succession of 5 times to uncover the root cause of an issue

• 5S exercises to sort and organize items, following the premise that there is a place for everything, and everything should be in its place.

Once the event has concluded, the participants should emerge with a list of recommendations for concrete, actionable solutions that can be put into practice right away. Since it is the stakeholders themselves who developed these solutions, there is typically a greater degree of acceptance for implementation.

Putting “Continuous Improvement”

Into Practice

While large manufacturers often employ experts to lead continuous improvement efforts, such as kaizen events, smaller manufacturers often do not have the background in that set of disciplines, or the capacity to employ dedicated staff with that skill set.

Fortunately, there are plenty of resources available. There are training programs, seminars, video series, and books specializing in these techniques. Many universities offer manufacturing extensions that provide low-cost consulting and training services to local businesses. Of course, there are skilled consultants eager to partner with manufacturers who are ready to begin their continuous improvement journey.

Conclusion

Many of these precepts can be implemented right away to yield positive effects, but it is helpful to view Continuous Improvement as a marathon. Committing to a marathon requires a marathon mindset. Anyone who has completed one knows that it is a life-changing experience. The hard-work required to achieve that long-term goal ultimately proves its worth. Similarly, there is more to kaizen than just the kaizen event or “workout.” A kaizen workout is just that… a workout. It is good for you. It will yield practical solutions to problems. But it is not the entire marathon. As one continuous improvement professional explains it, kaizen events solve specific problems, but more importantly, they teach employees how to become problem solvers. They help to nurture a passion for continuous improvement within your team. Teams who participate in a “culture of kaizen” will take ownership of their jobs with a mind toward creating value for the customer. That is what it is all about: developing a culture in which people — everybody in the organization — is trusted, empowered, and encouraged to play an active role in positive change. Everyone is fully engaged in bringing about an ideal state: maximum value for the customer. RF